Isla den Nos Bida

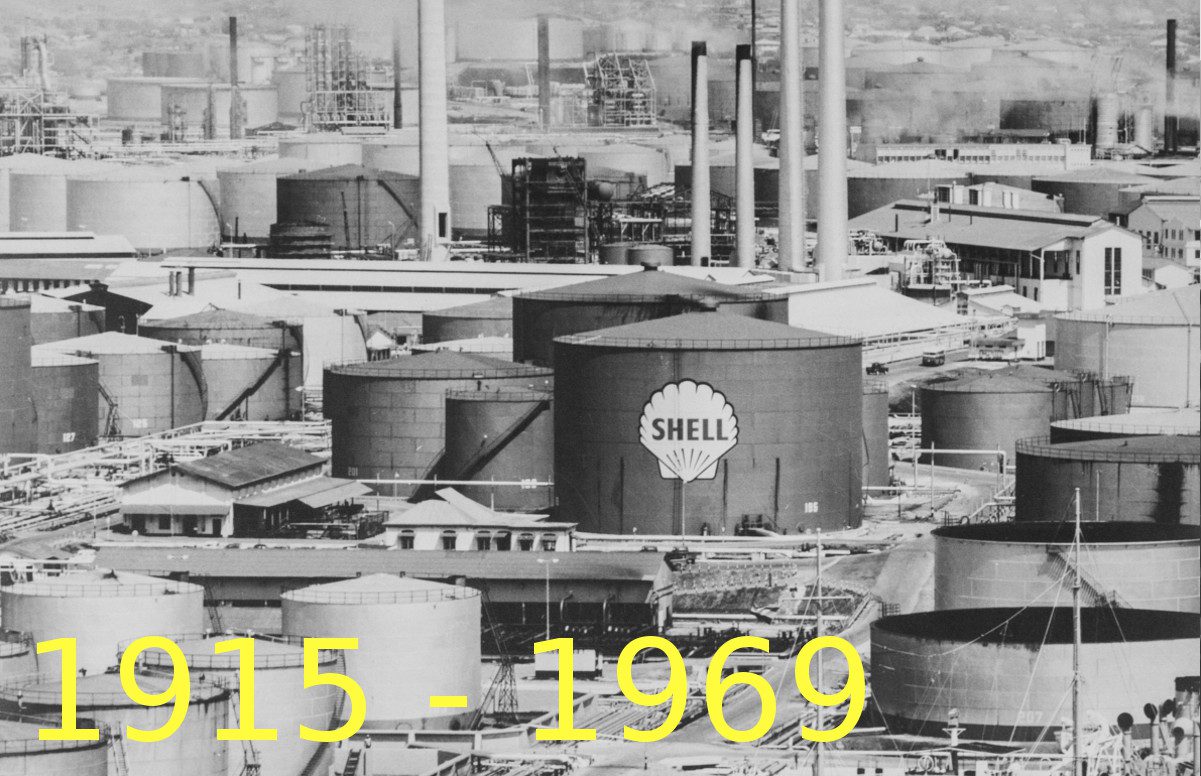

100 years Refinery in Curaçao – 100 aña Refineria na Kòrsou

Exhibition

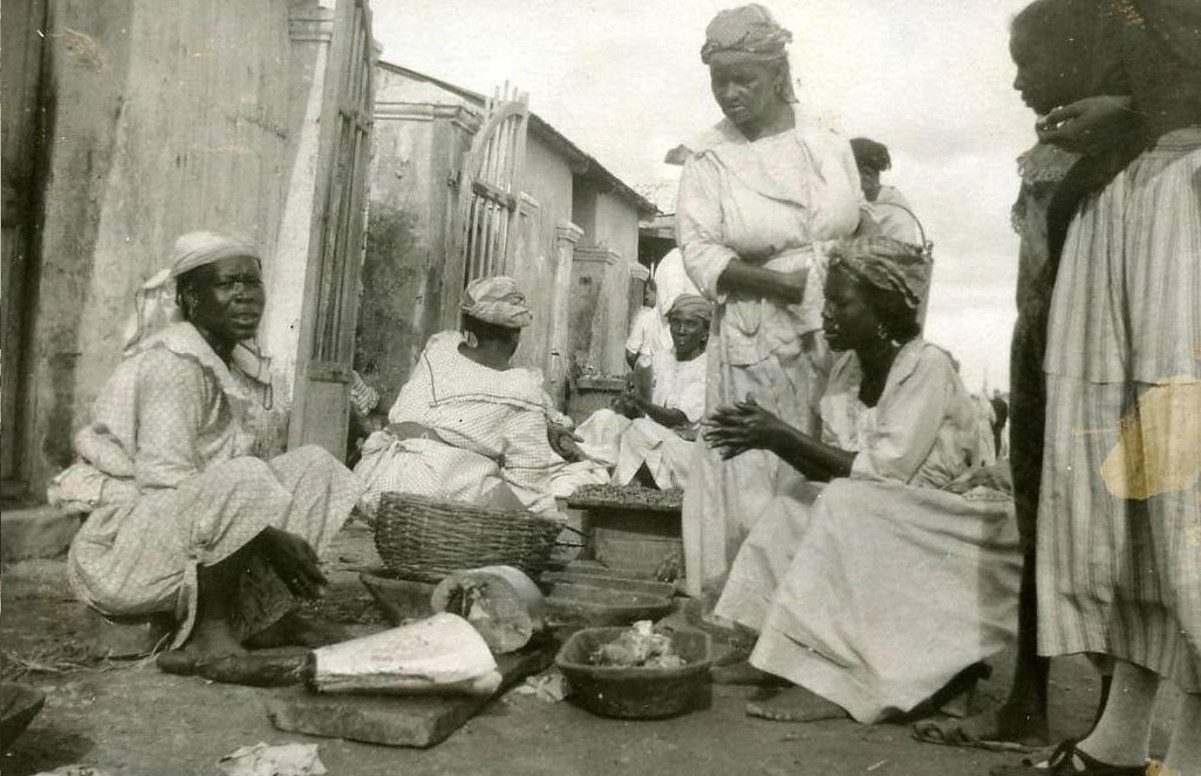

Curaçao before 1915

By the late 19th century, Curaçaoan trade was no longer as strong an economic pillar as it had been in the early days of Dutch colonial rule. As the colonial government reversed its policy on import duties, the harbor had lost its appeal as a ‘free zone’. In fact, by the 1900s, import duties had become government’s largest source of income.

This was much to the chagrin of Curaçaoan traders, who felt that government’s role should be limited to facilitating trade. The Chamber of Commerce, for instance, felt that “the sharp visitation.. in a building, which sports the word Customs in big letters, defames our former position as free zone.” Even so, the harbor’s central position in the island’s economy remained solid. “Curacao owes its existence, however meager, wholly to trade,” was the prevalent ideology of those leading society.

Curaçaoan trade was inherently an international affair. From the Netherlands came 20 percent of the Curaçaoan import. Beans and peas from the colonial center formed an aspect of the daily meals of the average Curaçaoan. From The Netherlands also came pottery, candles, dairy products and, of course, jenever (gin). Yet the United States was by far the largest supplier of goods. Corn, corn flour and wheat flour, both for local consumption and intended for the South American coast, came exclusively from the US. Venezuela supplied 60 percent of the local sugar consumption, and from the end of the 19th century also provided the few hundred cows imported as beef, which had previously come from Colombia.

Local Curaçaoan trade was also very diverse in character. In Punda, it was perfectly normal for one company to function as an agent for such various products as beer, sewing machines, insurance as well as selling sundries and shoes. Yet local production in the harbor suffered from competition in the region. Shipbuilding, for instance, was at an all time low due lower wages charged in Trinidad and Barbados.

On Klein Curaçao and the plantation Santa Barbara, British engineer John Godden started to mine phosphate from the late 19th century. A hiatus ensued after Godden came into conflict with the Gorsira and Maal families, who owned the plantation. In 1912, the issue was settled with the founding of the N.V. Mijnmaatschappij Curaçao, which continued the mining activities.

With the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, it was clear that the Curaçaoan harbor and economy needed an upgrade. Most steamships could hardly maneuver in the small thoroughfare to the St. Anna Bay. At the time, few realized a major industrial development was to transform the ‘destitute colony’ forever.