Isla den Nos Bida

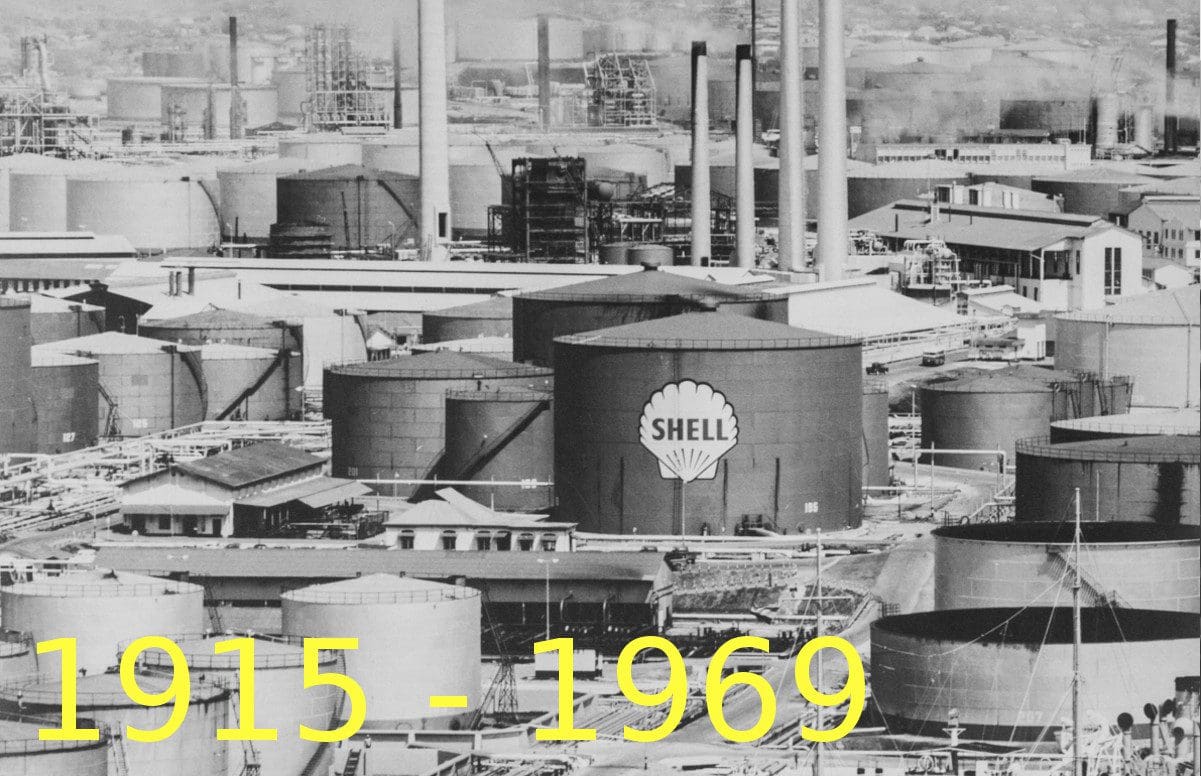

100 years Refinery in Curaçao – 100 aña Refineria na Kòrsou

Exhibition

1915 – 1969

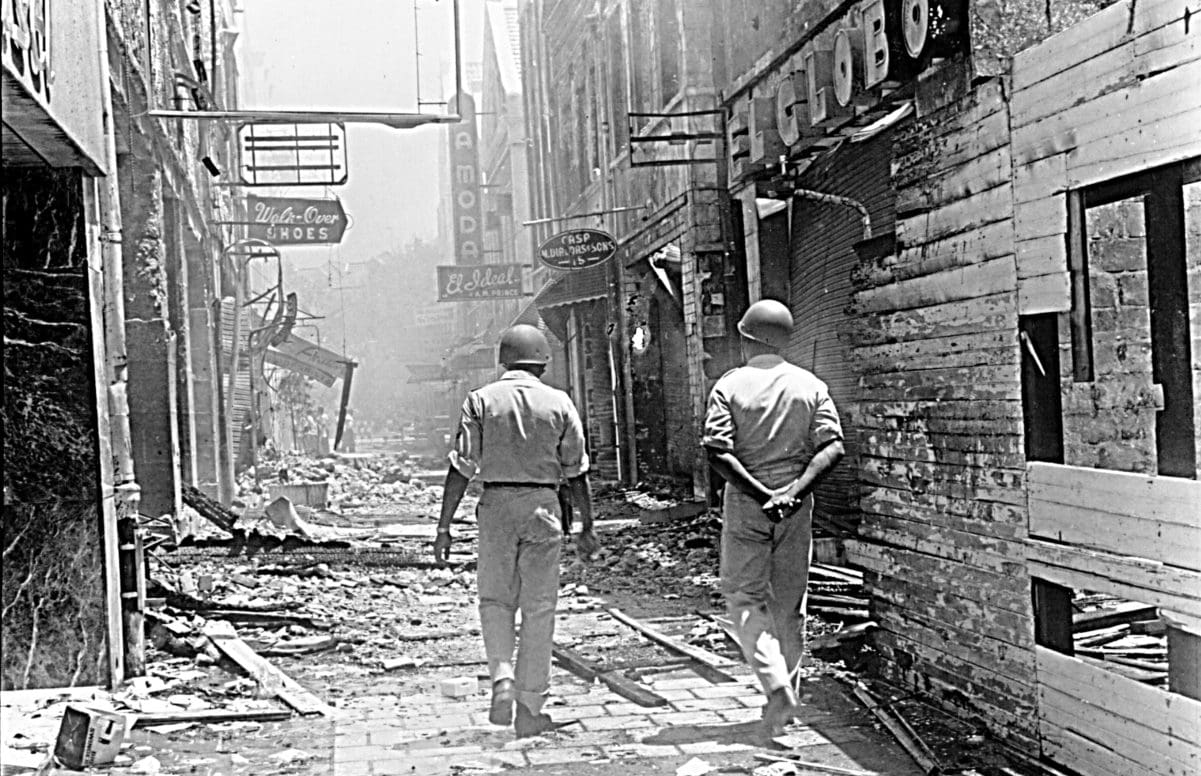

On the memorable day of May 30th, 1969, the refinery provided the flame which blew the inequalities within Curaçaoan society sky high. The conflict, which in a colonial setting aptly started as a labor strike for higher wages, quickly escalated into a racial revolt. Thousands of workers on their way from the refinery to plead their case in the government center Fort Amsterdam looted Hendersons, a grocery store which also sold hard liquor. Their anger, fueled by alcohol, released an ancient roaring inside their African souls. In that moment, they took a stand against centuries of racial and economic oppression. By the end of the day, two strikers lay dead, while Wilson ‘Papa’ Godett, one of the leaders of the movement, was in the hospital in critical condition. All were hit by police bullets.

Where the refinery had forever changed the Curacaoan landscape on all levels though aggressive expansion, CPIM now started to slowly withdraw, becoming an exceedingly smaller entity as it shed many of its former circles of influence. As one journalist put it: “The hypnoses of economic prosperity had worn off.” Economically, this retraction was most sorely felt by lower wage laborers. CPIM started to outsource many jobs to subcontractors, the largest being Wescar, a Werkspoor daughter company. However, Wescar only paid half of the hourly wage laborers had enjoyed working for CPIM. A lot of families found themselves in financial problems due to the severe pay cut.

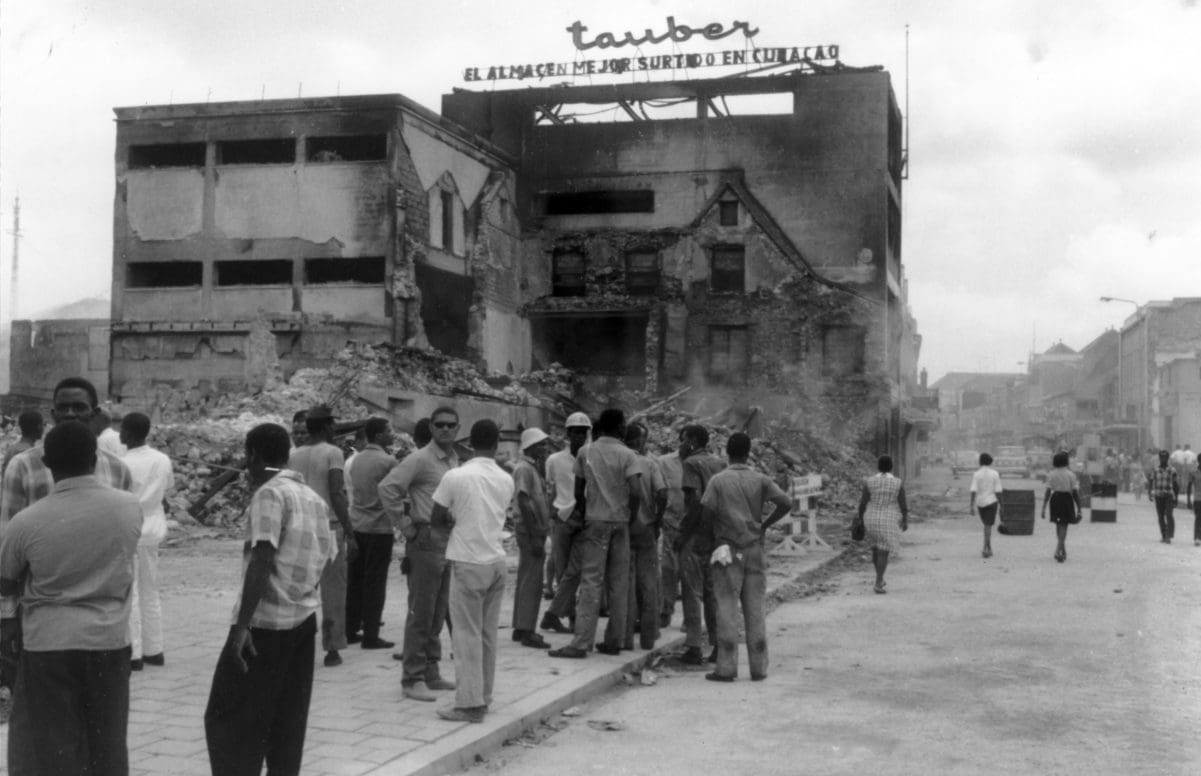

Material damage was extensive, as large parts of Willemstad were burned down to the ground. In Punda many stores were set aflame. Especially those owned by Ashkenazim Jewish owners, who had been targeted in publisher Stanley Brown’s Vitó. Brown, a schoolteacher who had been politicized while studying in The Netherlands, says the revolt was planned. The Bishop’s palace as well as many other buildings around Brionplein were also left in ruins. The psychological shock, for politicians, retailers and strikers alike, was huge. Never had the dark side of Curaçaoan existence showed its face so openly.

“The moment,” DP-parliamentarian J. Oenes said, “unions started to demand higher wages for Wescar workers, it was common knowledge Wescar wouldn’t be able to pay such a salary increase. Shell refused to provide financial backup. Not until a major part of Willemstad was going up in flames, Shell’s general manager signed the necessary papers.” That was at 4PM on May 30th, 1969. “All of a sudden, Shell found a way,” Oenes said.

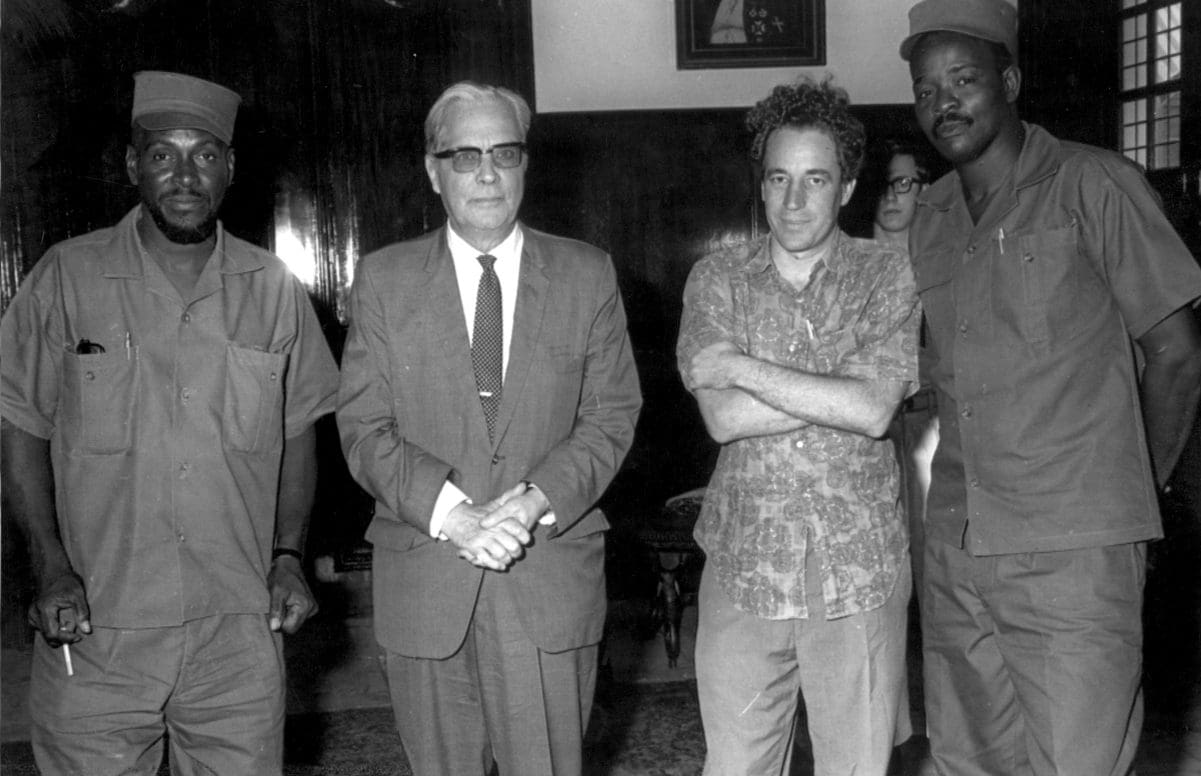

Yet the long term result was mostly positive. As strike leader and PWFC-secretary Ewald Ong-A-Kwie stated in the mid-1970s: “Prior to May 30th, 1969, a Curaçaoan worker was afraid of his superior, afraid of government. That changed. Employers also became more understanding toward workers. Antilleanization became a catch phrase.”

Due to the ripple effect of May 30th, 1969, this development extended outside the gates of the refinery. In September, 1969, Frente Obrero Liberashon 30 di mei (FOL), a political party founded by Godett, Brown and Amador Nita, won almost 23% of the vote. As a result, FOL occupied three seats in the new Antillean cabinet led by Ernesto O. Petronia, the first Afro-Antillean prime minister. Ben Leito and Anno Eligio Kibbelaar were installed as the first black governor of the Netherlands Antilles and Lt. Governor of Curaçao in 1970.