Isla den Nos Bida

100 years Refinery in Curaçao – 100 aña Refineria na Kòrsou

Exhibition

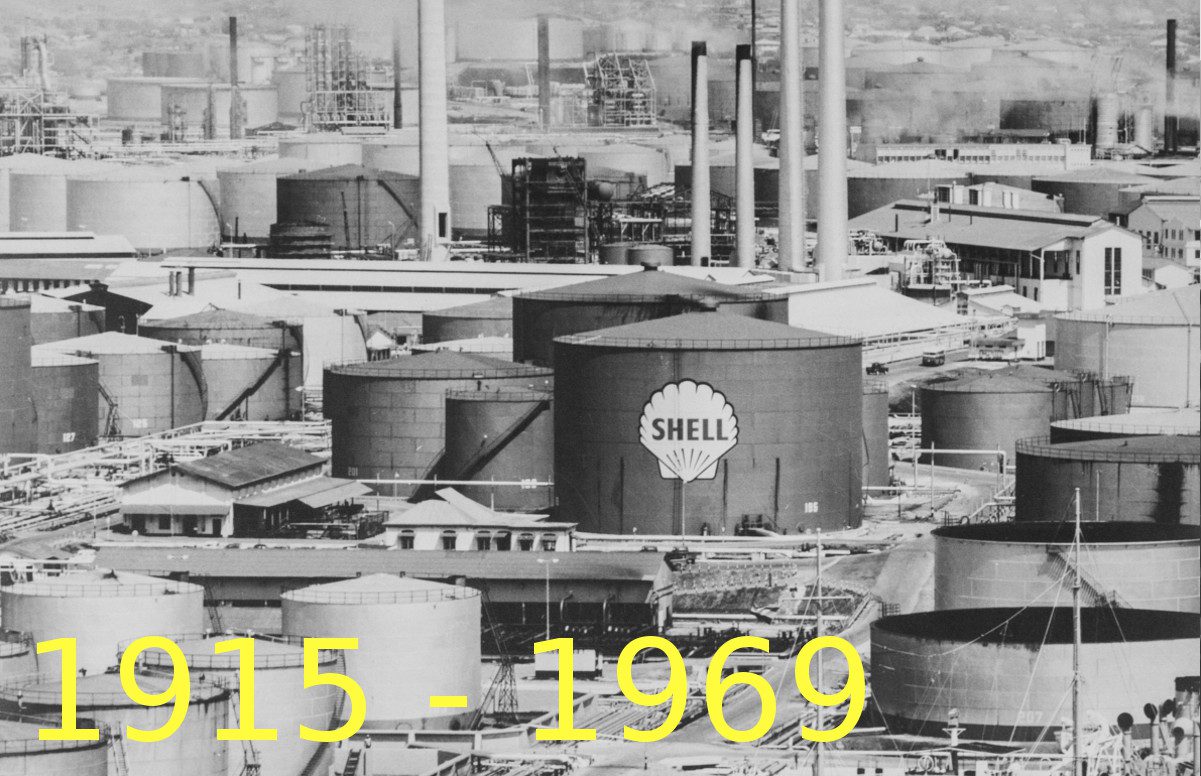

1915 – 1969

During World War II the Dutch government had been exiled to London, England. The colonies – Dutch East Indies, Dutch West Indies and Suriname – felt more freedom as the stringent Dutch colonial rule was suspended and the power dynamics were inverted. Now the wealth was generated in the colonies, supporting the Dutch government in exile, rather than the other way around.

Dutch Queen Wilhelmina, aware of the power shift, felt compelled to address the issue in a historic speech on December 6, 1942. Speaking on Radio Orange, which transmitted to the colonies, the Queen spoke of the need to revitalize Kingdom relations after the War. “Innovation is necessary in the constitutional construction of the Kingdom,” the Queen orated, speaking of future “Kingdom relations where the Netherlands, Indonesia, Surinam and Curaçao will jointly take part, while each will administer its own internal self government.”

This speech was mostly aimed at keeping on board the archipelago of East Indies, where Japanese forces were encouraging an independence movement. However, the Queen’s words strongly resonated in the West Indies. Indonesia claimed independence shortly after the war, while prolonged negotiations led to the birth of the new country Netherlands Antilles. Through a revision of the Dutch constitution in 1948, universal voting rights were introduced.

On Curaçao, the period of these negotiations leading up to the signing of the Kingdom Charter, or Statuut, was mostly experienced through the rivalry between the two main political parties Democraat and NVP. Where the Democratic Party led by Ephraim Jonckheer represented the economic interests of the white establishment, dr. Moises da Costa Gomez’ Nationale Volkspartij advocated the emancipatory plight of the colored communities. While Da Costa Gomez had prepared and negotiated the Statuut on behalf of the islands, the honor of actually signing the Kingdom Charter went to his nemesis Jonkheer, who’s Democratic Party had just recently won the elections. Publisher Oscar E. van Kampen detailed the lenghty blow-by-blow political fights between Da Costa Gomez and Jonckheer as cartoons in his popular weekly magazine Lorito Real.

Finally, the Kingdom Charter was signed by Queen Juliana on December 15th, 1954, bringing the Netherlands Antilles, Suriname and the Netherlands together as ‘equal partners’ in a transatlantic Kingdom. As a result, the United Nations officially proclaimed decolonization of the islands complete and removed the Netherlands Antilles – albeit reluctantly and with a narrow margin – from the United Nations’ list of Non-Self-Governing Territories.

The newly formed Netherlands Antilles, consisting of Curaçao, Aruba, Bonaire, St. Maarten, Saba and St. Eustatius, charged ahead. Fort Amsterdam on Curaçao remained as its government center, as it had been in colonial times. The Netherlands Antillean parliament consisted of 22 seats; 12 for Curaçao, 8 for Aruba, 1 for Bonaire and 1 for the Windward Islands combined.

Due to the revenue generated by the refinery, Curaçao was the wealthiest, not only among the other Dutch Antillean islands but also in the Kingdom as a whole. In 1958 the per capita income on the island equaled 1.087 guilders, while the Netherlands trailed behind with 702 guilders. However, a decade later the novelty had ceased and the common dynamics had been reestablished. In 1968, the per capita income on Curaçao stood at 999 guilders, while in the Netherlands the average had become 1.475 guilders.