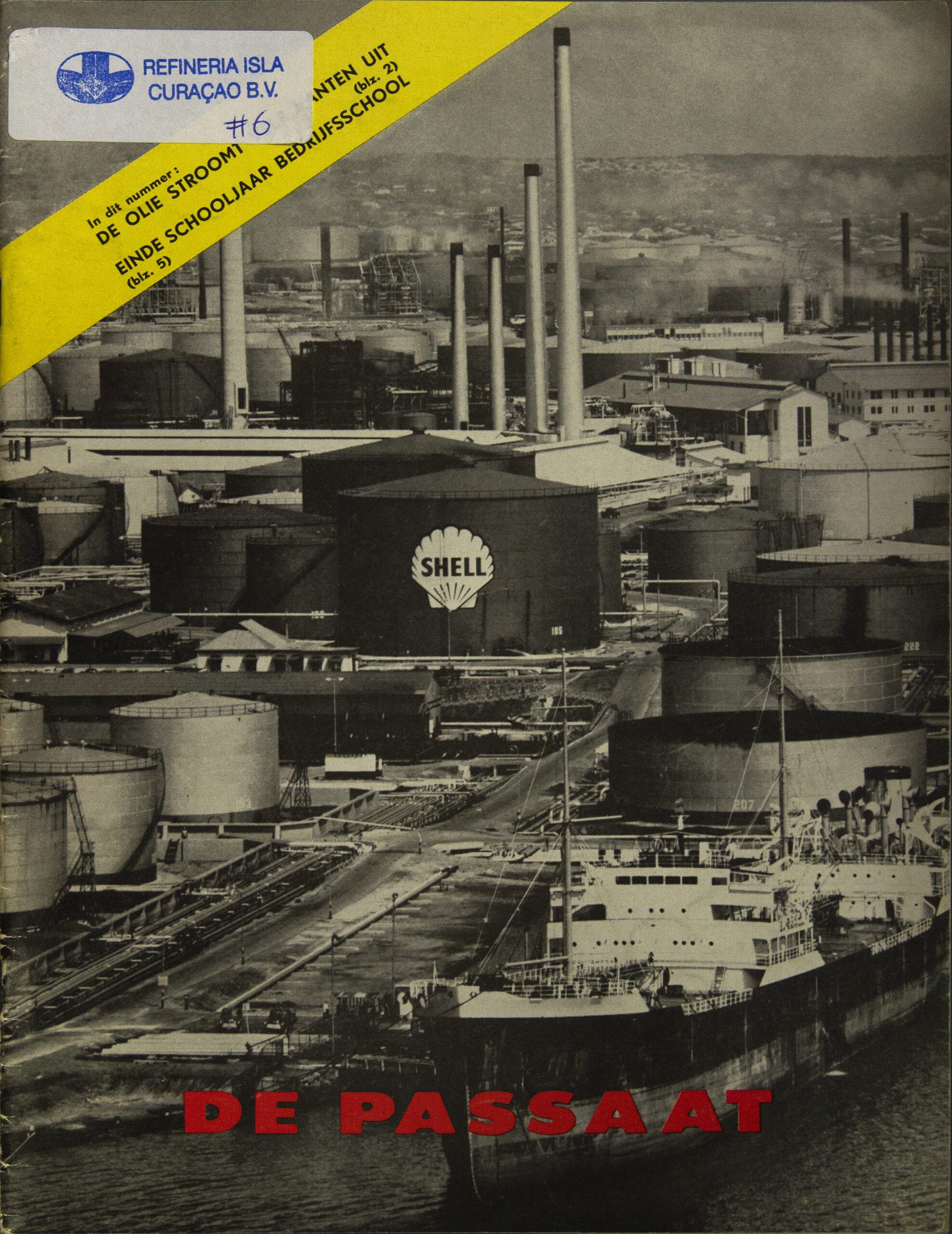

Isla den Nos Bida

100 years Refinery in Curaçao – 100 aña Refineria na Kòrsou

Exhibition

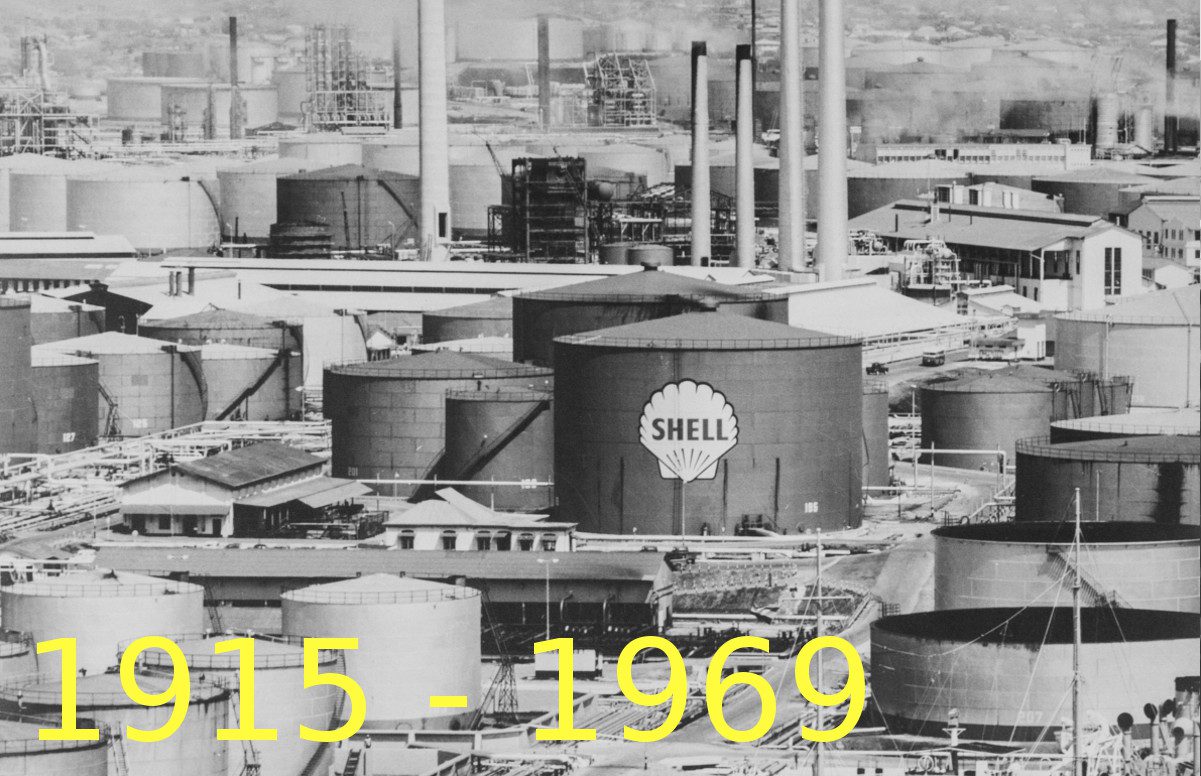

1915 – 1969

The influence of the refinery, and all that it entailed, reached far beyond its gates. Shell itself described it in a commemorative publication in 1965: “In 1915 the magic wand of industrialization transformed the idyllic natural environment of a pristine island.” Many new industries were created alongside the plant, facilitating the oil industry as well as the newly invigorated trade routes as a result of the rapidly expanding population. The refinery was warmly welcomed, as the oil industry banished the harsh circumstances of the late 19th century and diminished poverty. Even the nuns of the order of the Zusters van Roosendaal wrote when describing the plant: “The goose with the golden eggs” and “the oil tanks are cash barrels”.

However, the refinery substantially affected Curaçao’s geological make-up. One of the issues Royal Dutch Shell had all but overlooked when selecting the island was the refinery’s tremendous need for water. Initially water was secured at Asiento and through water concessions at plantations such as Valentijn. But CPM extracted more water from Curaçaoan soil than was strictly necessary, even selling tens of thousands of tons to outsiders. This practice was continued when, during the first period of expansion in 1923, water supply gradually became “rather critical”. CPM in 1924 bought the plantation Malpais, but quickly found it was a bad bargain. The comapny next acquired the more profitable plantations Brievengat, Zapateer and Cas Coraal. Two years later Groot Sint Joris was acquired.

By 1928, CPIM’s water consumption had risen to some 1.500 tons a day. A year prior, dr. J. Versluys had visited Curaçao to advise government on water supply issues. Based on Versluys’ recommendations, CPIM ordered a water distillation plant to be build and also bought the plantations Groot Piscadera and Klein Hofje in 1928. In addition, the refinery exceedingly started to rely on the arrival of European river water in the ballast tanks of empty freighters. Overall, the refinery greatly impacted Curacao’s soil, substantially dropping the natural water level.

Yet the financial trade off, both for the island in general and laborers in particular, was extraordinary. Salaries increased drastically, compared to the meager wages of pre-industrial times. But an irrevocably downward economic turn loomed on the horizon. CPIM ceased construction of company housing; it no longer required the labor of the oil worker migrant. It proceeded to create a company school, bedrijfsschool, to train superfluous personnel. The refinery’s first labor union Petroleum Werkers Federatie van Curaçao (PWFC) was founded in 1957.

At the end of the day – or rather by the end of the mid-20th century – it was Shell who’s influence ruled supreme navigating the economic waves of the island. Global economic trends often reached Curacao by way of the refinery. As authors J. Bakker & R. van de Veer pointed out: “Shell ran the island as the Dutch West Indian Company had intended: as a profitable company.”

These profitable economic trends, or high waves, swelled well into the 1950s. But when the global oil market started to change, and Shell’s presence on Curacao became less profitable for the company, the high waves came crashing down with phenomenal force in 1969, leaving destruction in their wake.