Isla den Nos Bida

100 years Refinery in Curaçao – 100 aña Refineria na Kòrsou

Exhibition

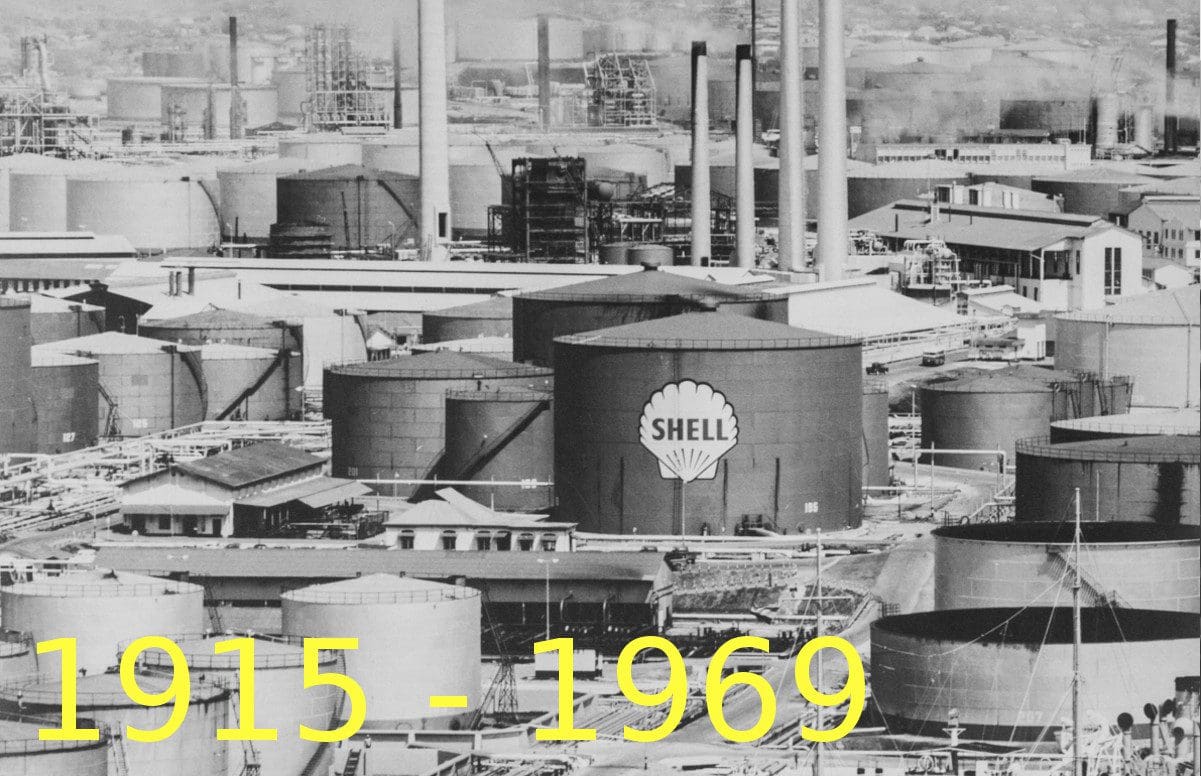

1915 – 1969

In the first half of the 20th century, the Curaçaoan population grew at a drastic pace. From almost 33,000 people in 1920, figures jumped with approximatly 25,000 additional inhabitants per decade. In the late 1960s the population reached a high point of some 145,000 Curaçaoans. By then, 42 different nationalities were represented turning Curaçao into a cosmopolitan center with many different ethnic groups. Most people came in connection with the economic surge engulfing the island with the growth and expansion of the refinery.

Migrants arriving from the Dutch Caribbean as well as the British and French Caribbean islands, the Portuguese island of Madeira, Colombia, Surinam,Venezuela, the Dominican Republic and the Netherlands, were tied to specific jobs, living arrangements and socioeconomic standing within the Curaçaoan society.

Until 1924, the refinery’s workforce consisted solely of Dutch Antilleans, Surinamese and European Dutch personnel. By 1925 lower class laborers from the Netherlands, the so-called pletters, were also hired. Subsequently, Venezuelan workers followed, who launched the first wage strike in 1926. The strike was broken after four days, but led to the departure of 200 laborers. Workers from the British West Indies, mostly from Trinidad, Barbados and especially the smaller British islands were more numerous. They were held in relatively high esteem by the white European executives and mostly worked as chauffeurs and security guards. They replaced many Surinamese migrants, who went on to work as teachers and policemen.

By 1929, cheap labor from the region was harder to come by. This compelled CPIM to recruit on the Portuguese island of Madeira. The first 50 Portuguese laborers arrived in September 1929. By 1938, there were more than 2.500 Portuguese, at that time 42% of all workers in the company. Although much appreciated and mostly deployed to do hard and backbreaking work, the Portuguese remained a marginal group in and around the refinery. As social geographer Charles Do Rego put it in his standard work on this subgroup, the Portuguese were “the last to be hired and the first to be fired.”

A less prominent group, although equally if not more influential in shaping the future of Curacao society, were women from the British Caribbean, hired to work as maids in the households of Dutch families. Until 1938, the colonial government upheld a restrictive policy regarding these women. However, under pressure from CPIM the policy was lifted, citing the “tight labor market concerning maids and the unreliability of local Afro-Curaçaoan women.” Due to the matriarchal Curaçaoan family structure and the tough socioeconomic conditions which persisted for a large group of Curaçaoan women, many were not in a position to leave their children and households to go clean someone else’s.