Isla den Nos Bida

100 years Refinery in Curaçao – 100 aña Refineria na Kòrsou

Exhibition

1985 – today

When PdVSA took over the management of the refinery in 1985, all parties involved knew that large scale maintenance was essential. To get the plant operating under modern standards by 1990, an investment of 600 million dollars was needed. Yet neither the Dutch government, Netherlands Antillean government nor Venezuelan government was willing or able to make such a large sum of money available. While various maintenance and upgrading programs were executed in an attempt to make the refinery smoother and more profitable, the necessary large scale modernization was never realized.

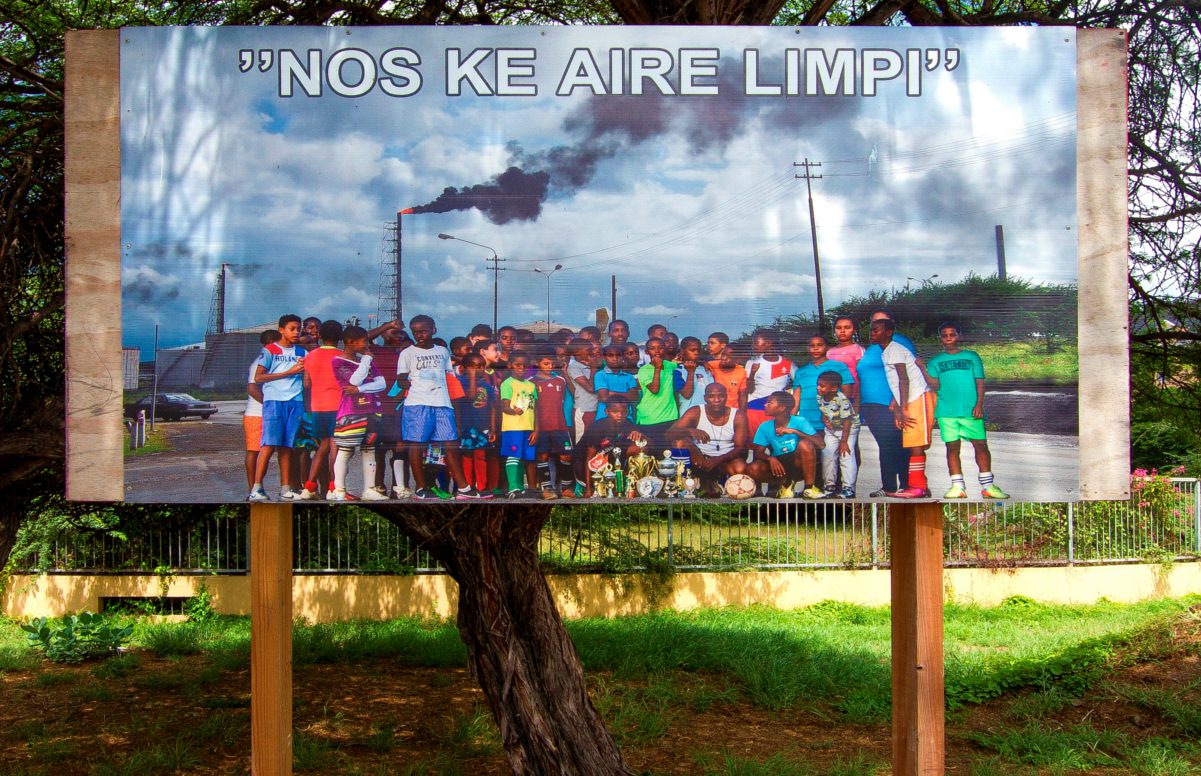

In 1989, Defensa Ambiental along with Komishon di Akshon Wishi/Marchena i Besindario organized a large scale street protest against the pollution caused by the refinery. Some 200 people took the streets in Wishi and Marchena to rise up against the poisonous fumes they were exposed to on a daily basis.

By 1994, production figures and profit margins were up. After three years of negotiations, a new lease contract between PdVSA and the Antillean government was signed on September 15th of that year. “I hope it’s going to be a very long honeymoon. We are going to be a champion refinery,” PdVSA-representative Luis Urdaneta commented. The new lease contract was to expire in 2019, and required PdVSA and the Antillean government to invest 220 million guilders and 110 million guilders in maintenance, respectively. Curacao could not realize an upgrade of 1.37 billion dollars, which would include an environmentally friendly flexicoker.

In 1995, the Dutch press started to show interest in the refinery, mostly the Asphalt Lake, a World War II legacy. The main question was whether Shell could be held accountable for the pollution left behind on Curaçao. Yet the company had been made exempt of all claims upon its departure in 1985. “That was a wrong move,” Lloyd Narain, president of the environmental activist organization Defensa Ambiental said recently. “It demonstrates that the refinery is too big and complex an issue for such a small island. The government lacks a vision for the future. It just lives day-by-day.”

Starting in the late 1990s, pharmacist Peter van Leeuwen and his SMOC activist group began preparations to take government to court in order to enforce the Public Nuisance Act. SMOC found that the refinery released toxic substances exceeding the stipulated limits. During the lengthy court proceedings, SMOC was justified in its claims several times. The Government stated that for the permit to be enforced, the refinery would have to be closed. Meanwhile, adjacent schools are frequently evacuated when high concentrations of toxic substances give students head aches and make their eyes water.

Politician and activist Norbert George’s Foundation Humanitarian Care Curaçao has filed a legal claim against Refineria Isla for 75 million guilders on behalf of 22 Curaçaoans living close to the refinery. A study by Nye Ecurys has shown that the pollution spewed by the refinery annually causes 18 premature deaths in Curaçao. More recently, action groups such as Stop Isla Now!!! have taken to the streets to protest pollution. Awareness of environment damage to the environment by PdVSA was also raised after an oil spill from COT reached the protected wetlands area of the saliña of Jan Kok at St. Willibrordus in 2012. Several flamingoes and much other wildlife perished due to oil contamination.