Isla den Nos Bida

100 years Refinery in Curaçao – 100 aña Refineria na Kòrsou

Exhibition

1969 – 1985

Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, the Curaçaoan educational system became influenced by young Curaçaoan teachers, who had studied in the Netherlands and brought more liberal and innovative ideas upon return to the island. These teachers mostly found work in the public schools supervised by government. On the other hand, the Catholic Church remained a powerful factor in the world of education through the Roman Catholic School Board. Yet the number of friars actually teaching and active in and around the classroom declined rapidly during the 1970s and 1980s.

The Mammoetwet, or Law on Secondary Education which had been implemented in the Netherlands in 1968, went into effect on Curacao as well. This law changed the existing structure of MMS (for girls), MULO and HBS into MAVO, HAVO and VWO. Vocational training, such as LTS and LBO also became more structured as a result of the Mammoetwet. Even though education was not compulsory in the Netherlands Antilles until 1991, a high percentage of children attended school during the 1970s and early 1980s.

Yet while many educational blue prints were adopted from the Netherlands, Dutch as language of instruction remained an obstacle for most students. In the 1960s, the Frairs of Tilburg even introduced a special 16-part instructional method for the Netherlands Antilles named Zonnig Nederlands (Sunny Dutch) to alleviate the problem. But as scholar A.F. Marks noted: “The linguistic diversity makes for a considerable degree of inefficiency, as children that grow up in Papiamentu speaking households are confronted with education in a language that is foreign to them once they start school. Whereas in the Netherlands approximately seven children out of ten reach sixth grade without repeating classes, in the Antilles not even one in four succeeds in doing so.”

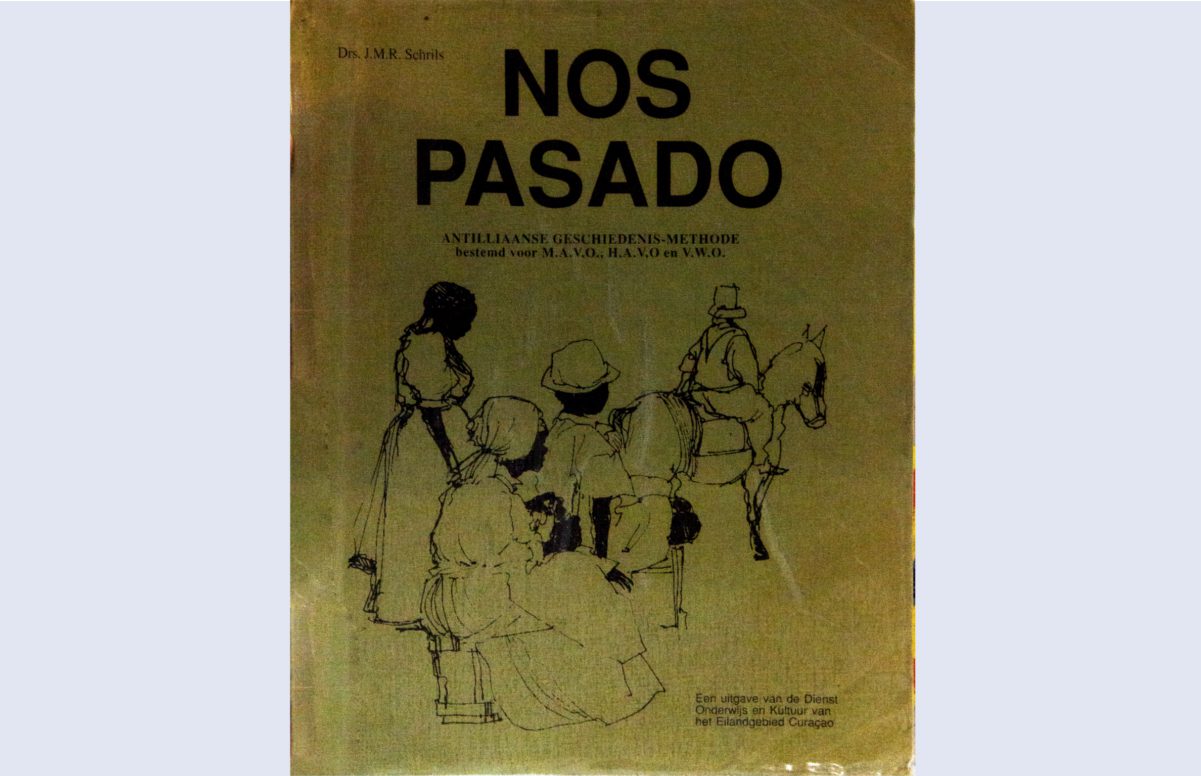

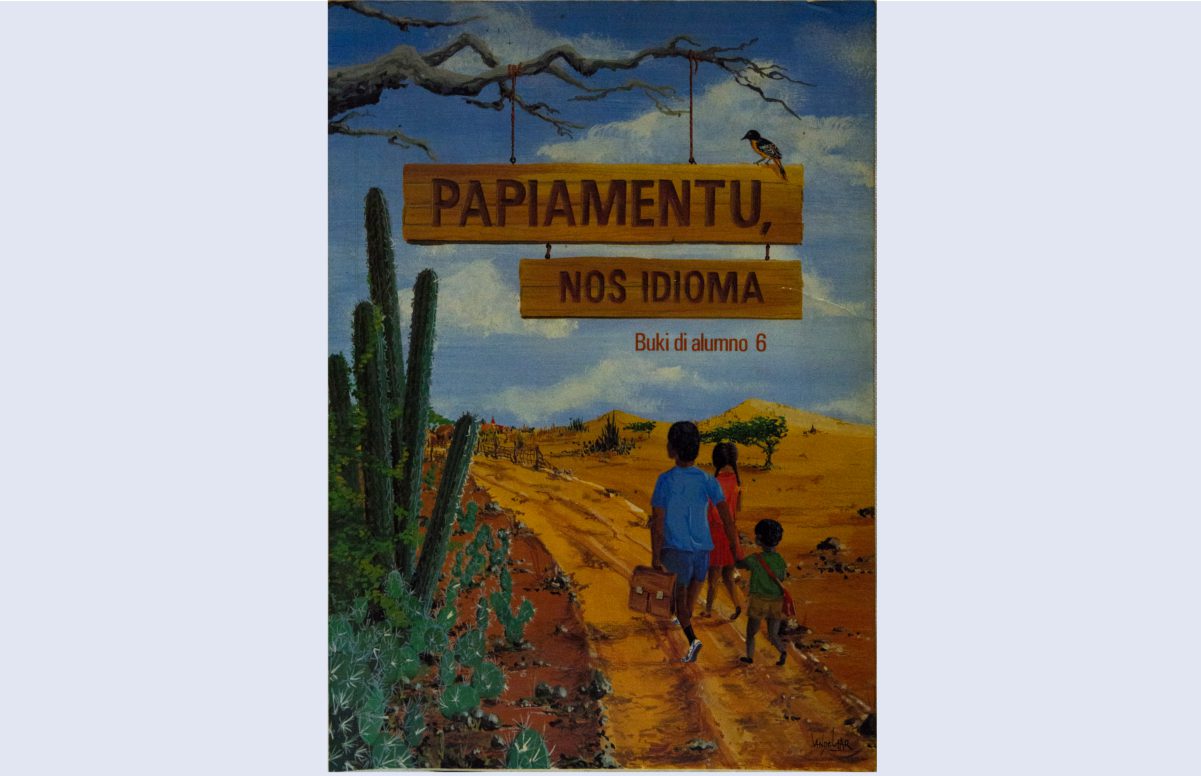

In Curaçaoan multilingual society, Dutch had always been the dominant language in schools, overshadowing Spanish and English and excluding Papiamentu. Addressing these problems in light of the events of May 30th, 1969, historian James Schrils developed the educational history books Nos Pasado, thereby triggering the discussion concerning Papiamentu as a language of instruction. In addition, the Instituto Lingwístiko Antiano (ILA) headed by Frank Martinus Arion stimulated and coordinated the use of Papiamentu. In 1986, Papiamentu was introduced as a subject in primary schools and in 1998 in secondary schools. In 2001, Skol di Fundeshi (Basic Education) was introduced in primary schools, embracing Papiamentu as language of instruction.

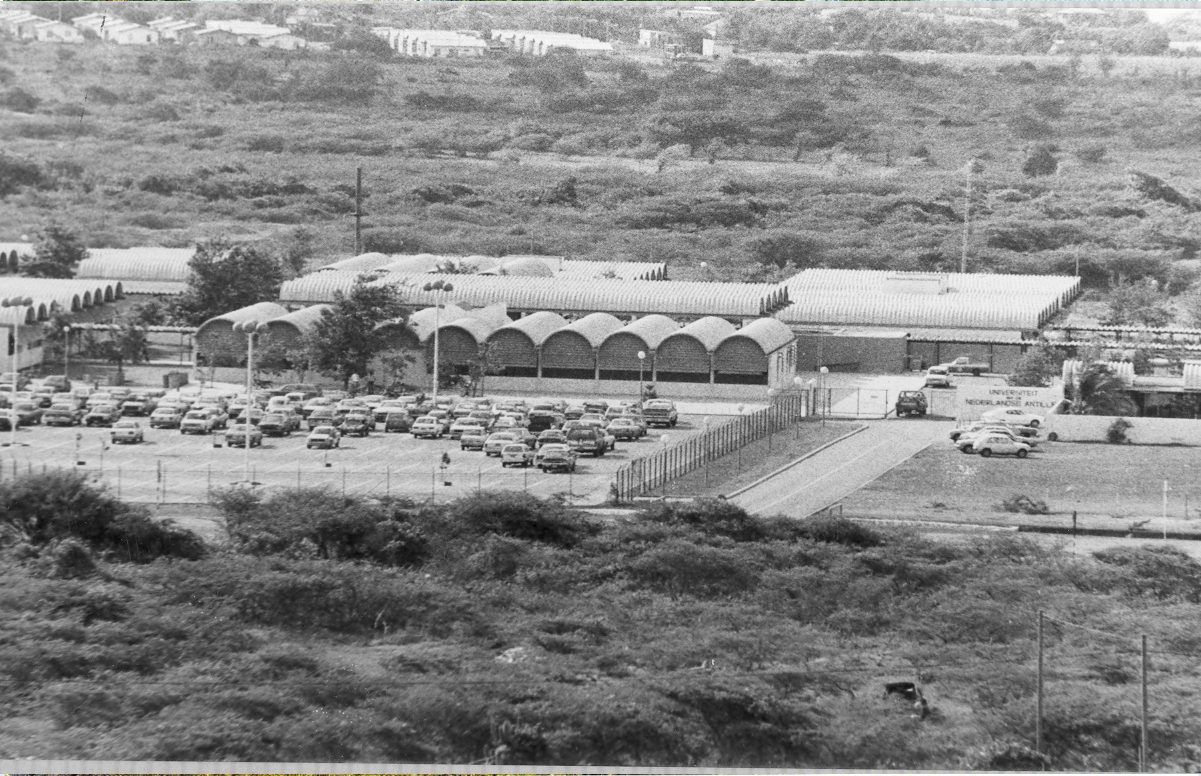

In terms of higher education, the University of the Netherlands Antilles opened its doors in 1973, offering students more education opportunities without having to move abroad. The Archeological Institute Netherlands Antilles (AINA) was founded in 1967. In 1977 it was expanded to include anthropological studies and the institute was renamed AAINA. Stichting Caraïbisch Marien Biologisch Instituut (Carmabi), orginally founded in 1955 for ocean research, saw its function expanded in 1982 when it was put in charge of performing academic studies for the complete Curaçaoan environment.

In 1990s, several private institutes for higher education found fertile ground on the island. They were geared towards Curaçaoan and foreign students, and focused on medical and business educations. As a reaction to the developments in primary and secondary education, including Papiamentu as language of instruction, various private schools established roots. This is an indication of the political and linguistic battleground education has become in Curaçao.