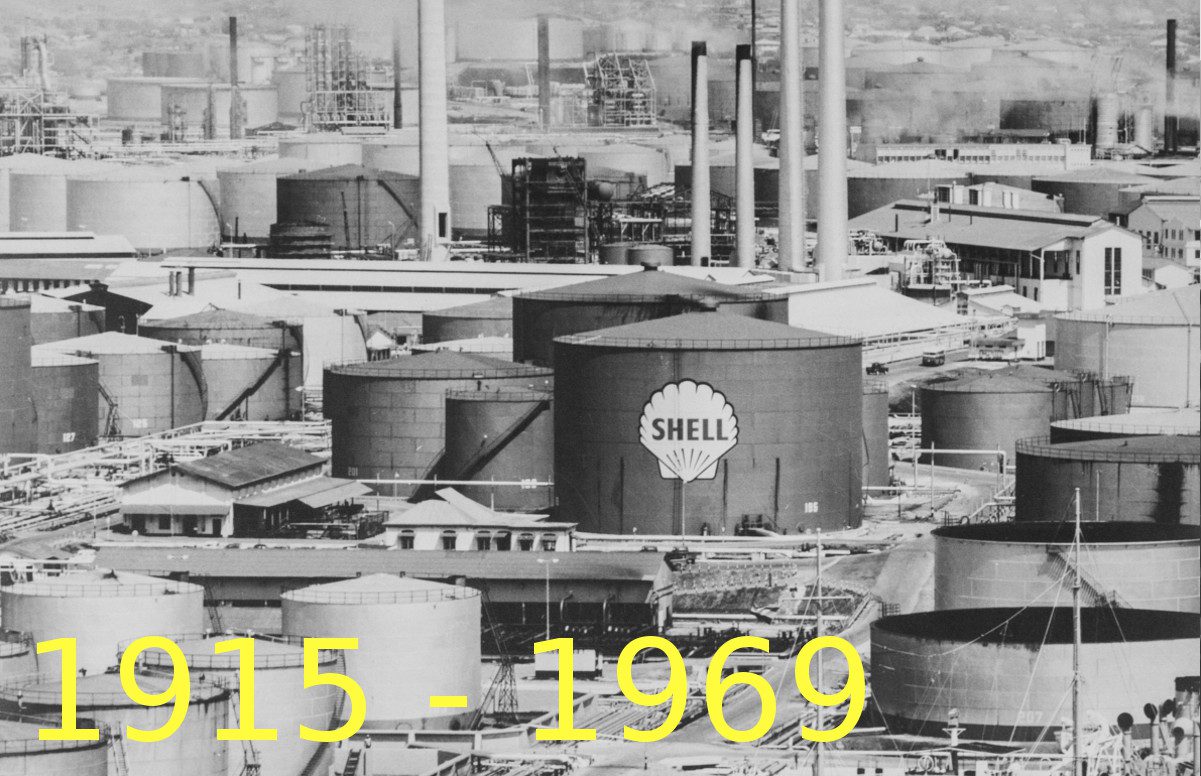

Isla den Nos Bida

100 years Refinery in Curaçao – 100 aña Refineria na Kòrsou

Exhibition

1969 – 1985

By 1970, the number of people directly employed by Shell had declined to 3.465 laborers. For the first time in its history, Curaçao was confronted with unemployment. The number of workers without a job rapidly grew to some 15%. After decades of prosperity, the fragile reality of the island’s mono-economy was hard to bear. Government was faced with the urgent task of economic diversification.

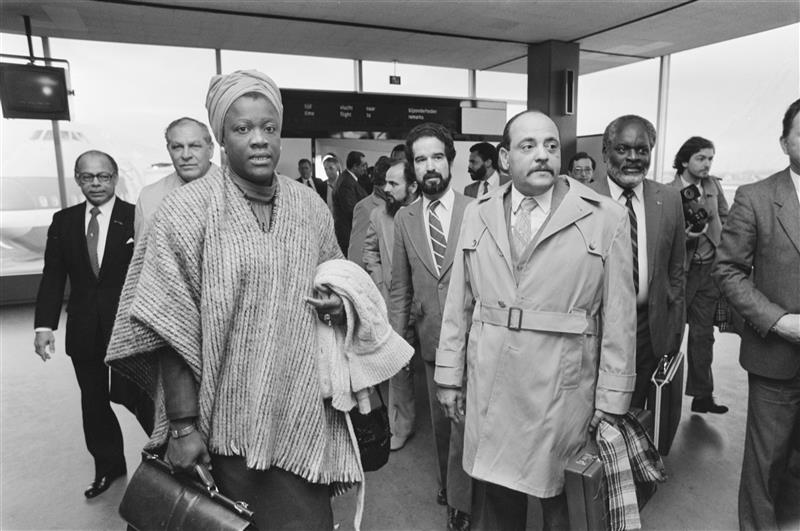

Yet there were favorable developments as well. In the mid 1970s, then Commissioner of Finance Don Martina – aided by future Dutch Minister Willem Vermeend – introduced a new form of tax, charging Shell Curaçao N.V. for pollution of the horizon and environment. Martina: “Curaçao always reasoned that what worked for Shell, worked for Curaçao. But the social needs are rising and I am of the conviction that companies should help alleviate that need. We have been renting out our house too cheaply.” Martina had a history with CPIM, where he had stood up to racial discrimination as an intern in 1954.

By 1980, Martina was by then prime minister of the Netherlands Antilles, the tax assessment had risen to some 23 million guilders annually. When Shell took the case to court the tax levy was rendered null and void. Yet in 1982, Curaçao and Shell reached a settlement, absolving Curaçao from having to reimburse any of the paid taxes.

But these were smaller victories against an ever darkening sky. By 1978 the number of people working at Shell Curaçao N.V. had declined to 3.000. And while in 1979 the company still made 220 million guilders in profit on Curaçao, by 1982 only losses were incurred. As of 1984 only half of the processing plant was still in operation.

On September 25th, 1985 the transfer agreement concerning the refinery complex between Shell and the Netherlands Antillean government was signed. Then prime minister Maria Liberia-Peters agreed to pay one guilder each for the complex’s four subsidiary companies: the refinery, the oil terminal (COT), the dry dock and the trading enterprise. COT and the refinery were immediately leased to the Venezuelan state oil company PdVSA. The dry dock and the trading enterprise were converted into government entities, named Curaçaose Dokmaatschappij and Curoil, respectively. Shell was left paying 86 million dollars for all personnel redundancy agreements, under the condition that the company was exempt of all future claims, including environmental petitions. This allowed Shell to leave Curaçao behind indefinitely.

On Curaçao, Maria Liberia-Peters still stands behind her decision. “I’d do it again,” she said in a recent interview. “We lacked the means to influence the discussion between Shell and Venezuela in a way that was more positive for Curaçao. And initially, the lease was only supposed to last five years. That gave us time to make adjustments and develop new sources of income.” During the transfer discussions, the Antillean government had had its back against the wall. Many Curaçaoans were glad all out closure of the refinery had been prevented.

But Shell’s departure from Curaçao triggered many to emigrate to the Netherlands, where the economy and quality of life were thought to be better and higher. This exodus would over time cause tension, both on Curaçao as well as in the Netherlands.